Thanks go to Catherine, Jill and Eileen for coordinating our day today. We started our day with a tour of the New Jersey Maritime Museum on Dock Road in Beach Haven, NJ. Deborah Whitcraft, Curator, began our tour with her favorite room – The Morro Castle, for which she has spent a good portion of her life investigating and researching the events that took place on that tragic day when the Morro Castle caught fire off the coast of Asbury Park, NJ.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

SS Morro Castle was a luxury ocean liner of the 1930s that was built for the Ward Line for runs between New York City and Havana, Cuba. The Morro Castle was named for the Morro Castle fortress that guards the entrance to Havana Bay. On the morning of 8 September 1934, en route from Havana to New York, the ship caught fire and burned, killing 137 passengers and crew members. The ship eventually beached herself near Asbury Park, New Jersey, and remained there for several months until she was towed off and scrapped.

The devastating fire aboard the SS Morro Castle was a catalyst for improved shipboard fire safety. Today, the use of fire-retardant materials, automatic fire doors, ship-wide fire alarms, and greater attention to fire drills, and procedures resulted directly from the Morro Castle disaster.

The final voyage of Morro Castle began in Havana on 5 September 1934. On the afternoon of the 6th, as the ship paralleled the southeastern coast of the United States, it began to encounter increasing clouds and wind. By the morning of the 7th, the clouds had thickened and the winds had shifted to easterly, the first indication of a developing nor'easter. Throughout that day, the winds increased and intermittent rains began, causing many to retire early to their berths. Early that evening, Captain Robert Willmott had his dinner delivered to his quarters. Shortly thereafter, he complained of stomach trouble and, not long after that, died of an apparent heart attack. Command of the ship passed to the Chief Officer, William Warms. During the overnight hours, the winds increased to over 30 miles per hour as the Morro Castle plodded its way up the eastern seaboard.

At around 2:50 a.m. on 8 September, while the ship was sailing around eight nautical miles off Long Beach Island, a fire was detected in a storage locker within the First Class Writing Room on B Deck. Within the next 30 minutes, the Morro Castle became engulfed in flames. As the fire grew in intensity, Acting Captain Warms attempted to beach the ship, but the growing need to launch lifeboats and abandon ship forced him to give up this strategy. Within 20 minutes of the fire's discovery (at about 3:10), the fire burned through the ship's main electrical cables, plunging the ship into darkness. As all power was lost, the radio stopped working as well, so that the crew were cut off from radio contact after issuing a single SOS transmission. At about the same time, the wheelhouse lost the ability to steer the ship, as those hydraulic lines were severed by the fire as well. Cut off by the fire amidships, passengers tended to gravitate toward the stern. Most crew members, on the other hand, moved to the forecastle. On the ship, no one could see anything. In many places, the deck boards were hot to the touch, and it was hard to breathe through the thick smoke. As conditions grew steadily worse, the decision became either "jump or burn" for many passengers. However, jumping into the water was problematic as well. The sea, whipped by high winds, churned in great waves that made it extremely difficult to swim.

On the decks of the burning ship, the crew and passengers exhibited the full range of reactions to the disaster at hand. Some crew members were incredibly brave as they tried to fight the fire. Others tossed deck chairs and life rings overboard to provide persons in the water with makeshift flotation devices. Only six of the ship's 12 lifeboats were launched—boats 1, 3, 5, 9, and 11 on the starboard side and boat 10 on the port side. Although the combined capacity of these boats was 408, they carried only 85 people, most of whom were crew members. Many passengers died for lack of knowledge on how to use the life preservers. As they hit the water, life preservers knocked many persons unconscious, leading to subsequent death by drowning, or broke victims' necks from the impact, killing them instantly.

The rescuers were slow to react. The first rescue ship to arrive on the scene was the SS Andrea F. Luckenbach. Two other ships—the SS Monarch of Bermuda and the SS City of Savannah—were slow in taking action after receiving the SOS, but eventually did arrive on the scene. A fourth ship to participate in the rescue operations was the SS President Cleveland, which launched a motor boat that made a cursory circuit around the Morro Castle and, upon seeing nobody in the water along her route, retrieved her motor boat and left the scene.

The Coast Guard vessels Tampa and Cahoone positioned themselves too far away to see the victims in the water and rendered little assistance. The Coast Guard's aerial station at Cape May, New Jersey failed to send their float planes until local radio stations started reporting that dead bodies were washing ashore on the New Jersey beaches from Point Pleasant Beach to Spring Lake.

In time, additional small boats arrived on the scene. The major problem was that in the large ocean swells, it was very difficult to see people in the water. A plane piloted by Harry Moore, Governor of New Jersey and Commander of the New Jersey Guard, helped boats to find survivors and bodies by dipping its wings and dropping markers.

SS Morro Castle after the fire; photo taken from the seaward end of the Asbury Park Convention Hall pier, November 1934.

As news of the disaster spread along the Jersey coast by telephone and radio stations, local citizens assembled on the coastline to retrieve the dead, nurse the wounded, and try to unite families that had been scattered between different rescue boats that landed on the New Jersey beaches.

By mid-morning, the ship was totally abandoned and its burning hull drifted ashore, coming to a stop in shallow water off Asbury Park, New Jersey, late that afternoon at almost the exact spot that the New Era had wrecked in 1854. The fires continued to smolder for the next two days and in the end, 135 passengers and crew (out of a total of 549) were lost. The ship was declared a total loss, and its charred hulk was finally towed away from the Asbury Park shoreline on 14 March 1935, and, according to one account, later started settling by the stern, and sank while being towed up the river. In the intervening months, because of its proximity to the boardwalk and the Asbury Park Convention Hall pier, from which it was possible to wade out and touch the wreck with one's hands, it was treated as a destination for sightseeing trips, complete with stamped penny souvenirs and postcards for sale.

(Other accounts have it that the ship

was towed to Gravesend Bay on March 14, 1935, after serving as an Asbury Park attraction, and then to Baltimore on the 29th, where it was scrapped.

Pictured above is a lifejacket from the Morro Castle. Many of the passengers that jumped broke their necks when they hit the water because of the force of impact to the lifejacket. There were no safety drills at that time to teach the passengers to cross their arms over the lifejacket to keep it from breaking their necks.

In the photo above, you can see that the lifeboat is no where near at full capacity. The men pictured are crew and officers who fled the ship with no regard to the passengers. Deb informed our group that the Radio Operator (pictured below), George Rogers, is a prime suspect in the death of the captain as well as the person who started the fire. It was never proven, although it is widely suspected. He eventually died in Trenton State Prison in the 1950’s for murdering 2 people – unrelated to the Morrow Castle disaster.

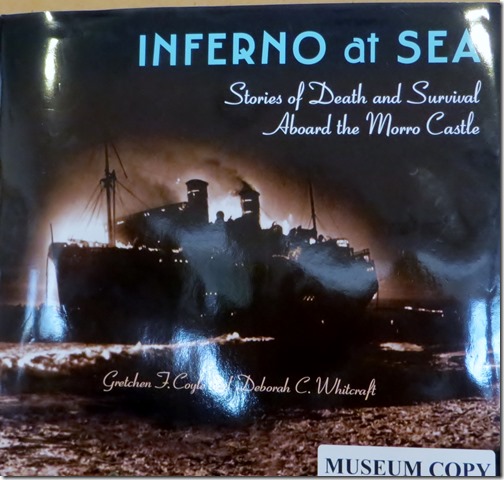

Deborah co-wrote the above book which is for sale in the museum gift shop.

The Coast Guard did not respond to help save the passengers, most of whom jumped off the burning ship. The Paramount, a small fishing boat run by the Bogan family, rescued many of the distressed passengers and brought them to shore. Deb has actually travelled to Cuba to continue her research and interview people who may know something about the circumstances of this horrific incident.

We continued our tour throughout the Museum with Deb offering interesting information about the wrecks that sit offshore of New Jersey and the artifacts that the divers are able to bring up.

Below is a sign that was in the cemetery in Smithville that needed to be replaced…….so Deb conveniently removed it with her own two hands (in the dark of the night) in order for it to be replaced with a new, more respectful sign.

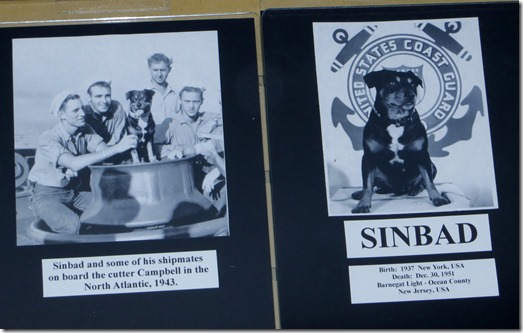

Above, Deb is telling us about Sinbad, an honorary Coast Guard Mascot……….

We all agreed that this tour was something we may have not done on our own (most likely not), yet we thoroughly enjoyed learning about the maritime history of the Jersey Shore. Many of us spoke of coming back with friends and family.

SS Andrea Doria

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The SS Andrea Doria, hours before she sank on July 26, 1956

SS Andrea Doria was an Italian ocean liner, or passenger ship. It was owned by a ship line called the Italian Line. It was said to be the biggest, fastest, safest, and most beautiful ship in Italy after World War II. It could carry 1,221

passengers and 563 crew.

The ship was built by the Ansaldo Shipyards in Genoa, Italy. It was launched on June 16, 1951. Its maiden voyage, or first voyage, was on January 14, 1953. Three years later in 1956, it crashed with another ship, MS Stockholm, in the Atlantic Ocean. At that time, 1,134 passengers and 572 crew were on board. Andrea Doria

sank in 11 hours, but Stockholm survived.

The Andrea Doria was the last large ocean liner to sink before airplane travel became popular.

OK – I couldn’t resist this pic!

Terry and I were surprised to see the model pictured above of the Vasa, a Swedish Warship that sunk on it’s maiden voyage in the year 1628. It was raised over 300 years later and is on display at the Vasa Museum in Stockholm, Sweden. We both recently returned from a trip in the Baltics and visited the Vasa Museum.

After our tour, we all went to Kubel’s Pub for a very nice lunch! Another great day!